🐿 The genderisation of sewing and maths. January meet up Sheffield, 2025, Script of Crone Verity’s talk (AKA the Crone That Counts)

Thank you, Justine, for letting me talk about my favourite subjects – maths, sewing and myself.

I’ll start with showing you a photo of three little girls sitting doing their sewing. I don’t know why my mother kept this photo. I found it when we were tidying up after she died. She’s carefully written on the back the names of the other two little girls doing their sewing, and the name of the primary school where it was taken. The little girl at the front on the right hand side is me.

I can tell you that it was taken in September when we were in third year juniors, what we call Year 5 now. I was just nine, one of the youngest in the class and I know all that because of the plaster cast on my wrist. That dates it pretty precisely. And what are we doing? I think we’re doing little bits of cross stitch and embroidery but it’s difficult to tell. There’s a box of scissors. we’re quite absorbed in our task unaware of the photographer. Why was the photographer taking photos? I really don’t know.

It’s a professional photograph, my mother obviously paid for a copy of it. I don’t know what the other children are doing. It looks as if that little boy behind us is more occupied by watching the photographer, and he doesn’t look as if he’s sewing. I’m pretty sure the boys didn’t do sewing. Don’t you love the little hand knitted cardigans we’re wearing? We didn’t have to wear school uniform in those days in village primary schools.

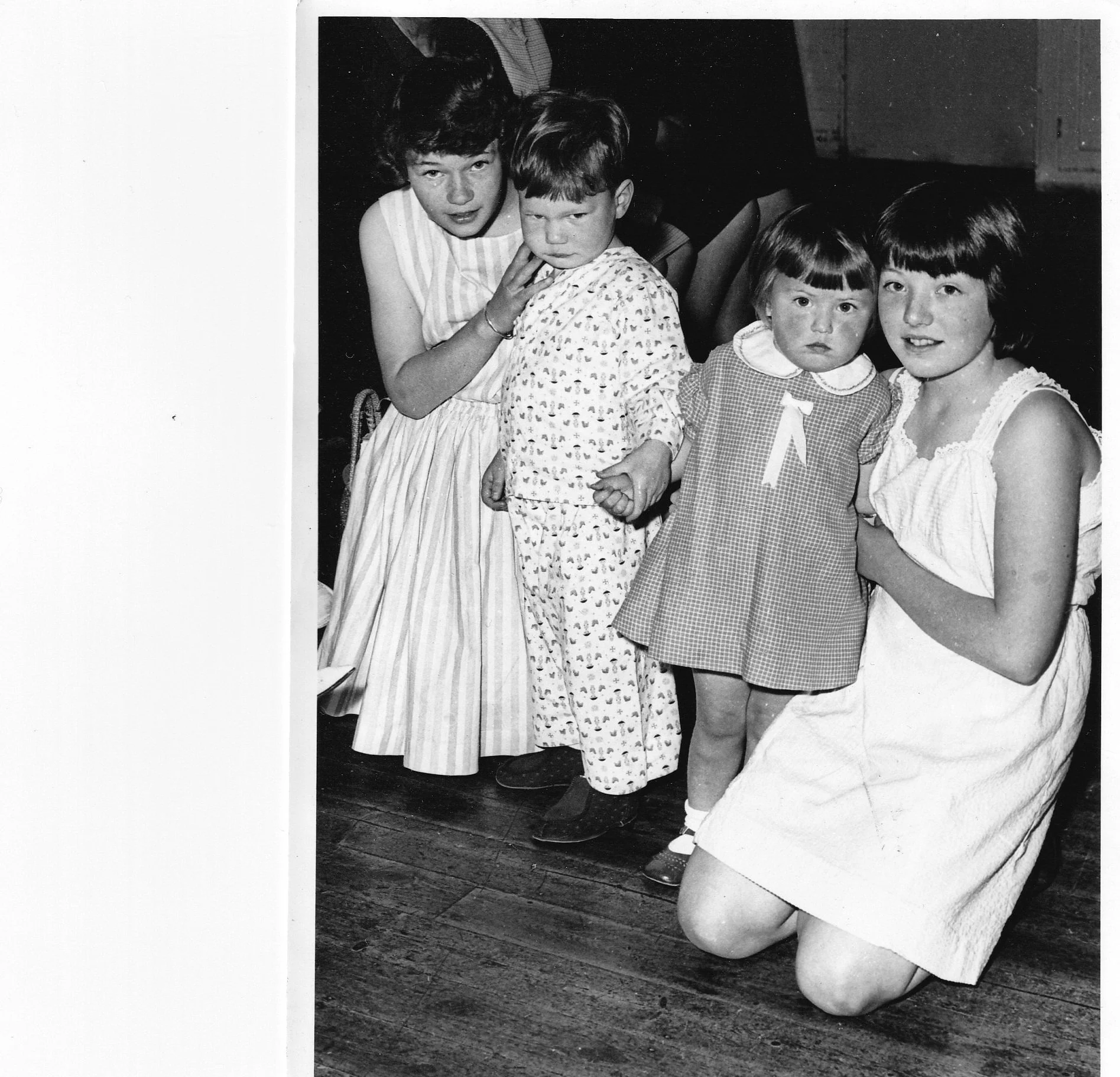

And here’s another photo.

This one’s from 1963. My mother kept it carefully along with the press cutting. I think I remember her going to a bit of trouble to get a print of the photo from the office of the Newark Advertiser. She kept the cutting as well as the print. The caption on the newspaper cutting says “Girls at a Southwell school made useful clothes for themselves last term - but two of them catered for younger members of the family as well as for themselves. Verity Mosenthal (left) made pyjamas for her 2 1/2 year-old brother Johnny and Karen Fletcher made a dress for her 2 1/2 year old sister Lindsay.” We were proud of our work. We’d had a little fashion show at the end of the year, and the newspaper came!

Every Wednesday afternoon Mrs Fox took the girls in the dining hall for sewing. By the time we left that school we could make clothes that we wanted to wear. We could cut out patterns and alter them to fit. I was quite proud of those pyjamas even if little Johnny is scowling. The top had a proper collar and buttons with button holes and the trousers had a little flap fly. The dress for Karen’s little sister has a perfect Peter Pan collar. The dresses and skirts that we’d made were clothes that we were willing to wear.

Mrs Fox taught us useful skills. I don’t know how common that was. I don’t resent the time I spent learning needlework at primary school. However when I went to secondary school, we started again from scratch as if we’d done no sewing at all. It was very frustrating because we had to make a little needlebook and a pincushion and a scissor case and then a very simple apron before we could get onto actually making anything, so I think that in those days in Nottinghamshire there can’t have been a standard curriculum prescribed. We had a similar experience in maths, starting geometry from scratch. I hadn’t ever seen compasses, protractors, didn’t know the names of shapes. I didn’t realise there was anything odd about not knowing,

It was much much later that I wondered what the boys had been up to on a Wednesday afternoon while the girls were sewing. Somehow, I found out that they were doing technical drawing!

And my last anecdote is from the nineties. I used to teach Maths in a comprehensive school and I once designed a task for a class of pupils aged about 15. They were a class that found maths challenging but still it wasn’t an optional subject. I gave them a task about making tabbards for netball.

They had sketches of the pieces - the pieces were rectangles and other simple shapes. They had to make a scale drawing on squared paper of how it all fitted together, and how to put the pattern pieces on the fabric so that they had the least waste, and they needed to name the shapes - rectangle trapezium and so on.

The boys couldn’t do it, they just froze. They didn’t understand the task. The girls got on with it. They didn’t do it very well, but they knew what they had to do. In fact I think some of them suggested modelling the task by cutting out the shapes themselves to scale on the squared paper and putting it on the grid. So a few weeks later I gave the same class the same set of shapes and this time they had a piece of MDF the same size as the piece of fabric, and they needed to cut these shapes out to make a box out of the MDF board. The boys had no trouble doing it and the girls found it quite difficult.

So what was going on? All of this is part of why girls have found maths difficult. If you’re given a practical problem but you don’t understand or aren’t interested in the context it can be hard to engage with it, and then it’s hard to work out what maths you need to solve it. Certainly when I was at school and university, the problems were quite masculine. Sports were usually cricket, the person was always male unless they were doing something silly. Nowadays there’s a lot of effort put into ungendering maths but there’s a long long way to go and a lot of prejudice still. Girls do as well as boys at GCSE – better in fact - but often they don’t carry on with Maths afterwards.

The “Common Threads” (1997) by Mary Harris helped to enlighten me. If we look at the past, women did needle work: upper class aristocratic ladies did embroidery called work. Jane Austen‘s characters would put down their ‘work’ when a visitor arrived. You can imagine the scene. And the rest, (before the middle classes existed), the servants and working women, they made clothes and sewed working clothes and they did mending and patching.

They all did loads of maths at the same time. Not just buying fabric and turning 2-D shapes into 3-D objects to go round our strange shaped bodies. Think how complicated that is. Think about curtains.

Think about the calculation of how much fabric is needed to get the gathers with the right fullness. And the spacing of the hooks along the tape. Women do it all the time and men dismiss it as simple maths. It’s not rocket science but it’s not simple.

If we think about things like embroidery there’s also an incredible amount of geometry incorporated in patterns. Here’s an illustration from “Common Threads”.

The top line has patterns found on a neolithic linen cloth in Switzerland; the middle one are traditional cross stitch designs from the holy land, and many of these were revived by Victorian cross stitch embroiderers; and the bottom one is designs worked by a woman called Hanna Canting in 1691 on a sampler that’s now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

So the leisured classes taught their daughters to sew while their sons went to school. And the sons learned classics and maths and some of them went on to study serious mathematics. That’s a part of why we had very few female mathematicians in history - they just didn’t go to school and they didn’t study maths. They had governesses who taught them how to do embroidery.

Once we have universal schooling, the astonishing thing is that this continued. There were charity schools, and they grew in popularity in the late 18th century. They had a Christian motivation aiming to replace a “deficient moral environment and the cause of poverty” with a more wholesome Christian one. There were also Dame schools which taught basic literacy and summing. In the 19th century, there were the schools of National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church – known as National Schools. Incidentally, the school where I was sewing on a Wednesday afternoon in 1963 was known as the National. I didn’t realise what that meant at the time. In the schools, mathematics was masculine and needle work, however much geometry or measurement or calculation it involved, was feminine and it wasn’t recognised as Maths.

I’ll give you a couple of quotes from “Common Threads”. The first is about the National Schools in the 19 th century.

They generally gave priority to boys. Boys and girls were originally admitted at different ages, could be charged different weekly fees, and be taught in different rooms, or separated in one large room by a partition and girls sometimes remained in the infant class as boys moved on up the school. Family gender roles could also be a major factor in girls’ access to schooling, for though both boys and girls were required to work at home, the requirement on girls for regular work like minding the baby or helping on washing day, was so widespread that it was accepted by schools. Truancy regulations were much less heavily imposed on girls than on boys. Whatever the local variation, it is safe to assume that overall, and for very many years, girls got less education, measured in hours than did boys.

And another.

The reality was that education itself had always been a thoroughly male affair and that girls, however numerous, were newly arrived extras in the expanded system. From then on, in official and educational parlance, there was ‘education’ and ‘girls’ education’, in a systematic usage that maintained women’s economic invisibility and sustained pathological interpretations of their biology.

To confirm their vocation, not as a worker but as a female, their curriculum was distinguished by the task that beyond all others signified their feminine, domestic role and where the boys followed the 3Rs, the girls followed 3Rs and 1N. No matter how traditional or radical, no matter how opposed to the domination of education by the Church, needlework for girls was the one thing that everyone agreed must be taught.

The idea that maths isn’t for girls is very deeply ingrained in our subconscious. It goes back a long way historically. These days girls do just as well at GCSE if not better than boys. But they don’t carry on studying it afterwards to the same extent. It’s been fun recently to see some female mathematicians have been using ideas with fabric to illustrate Maths. I’ve started to collect some books about it – women making amazing models solid shapes in several dimensions and some really sophisticated maths. Finally, here’s a YouTube video. It isn’t sewing, it’s crochet but it shows just how much maths there can be in women’s work.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lxKUuMxH8

Beautifully, beautifully bonkers.

Crone Verity aka The Crone That Counts giving her talk at the Crone Club Sheffield January Meet up 2025.

Big thanks to The Crone That Counts for giving the talk. We loved it. xxx