RIP the queen Crone of steel, kathleen roberts

Justine with Kathleen Roberts in August 2022 at her home in White Willows, Jordanthorpe. Pic credit Justine Gaubert

I set up Crone Club to surround myself with kick-ass older women to learn from their wisdom and remove some of the fear that was being fed to us on social media about getting older. We also wanted to reclaim ‘crone’ from being an insult, to instead mean ‘crown’ derived from the word ‘cronus’, meaning time, representing the wisdom older women can have.

This is why, in 2022, I was so delighted to meet Kathleen Roberts - AKA ‘Last Woman of Steel’… and was so sad to hear of her death last week, all be it at the wonderful age of 103.

For our crone sisters across the pond (and maybe some down south!), Kathleen Roberts was one of the Sheffield women who worked in Sheffield’s steelworks during World War II (called up aged 18). Then in her 80s, she became the public face of the ‘Women of Steel’ campaign to get those women recognised. After years of fundraising events that brought the city of Sheffield together, they raised over £170,000 for the ‘Women of Steel’ statue and medals for surviving women and families, gained official Government recognition, took tea at Number 10 with Gordon Brown, and, of course, gained eternal love and gratitude in the hearts of Sheffielders.

The Women of Steel at the unveiling of the statue at Barkers Pool in 2016. Pic credit The Star.

When I heard of her death, I dug out my audio interview with her from 2022 to pull together what crone lessons we can all learn from this amazing woman and her incredible generation. Huge thanks to her daughter Julie and granddaughter Louise for checking it over and for your lovely feedback. We are thinking of you this week. xxx

Note: (If you’re also a paid subscriber of The Tribune 🙌, this is the Unabridged-Long-Read-Crone-Director’s-Cut, just for our paid subscribers 😘 A massive thanks to you all).

Crone lesson 1. Humility

“I should think the people of Sheffield have had enough listening about me” says Kathleen, as she settles into her sofa on a boiling hot day in August 2022. Thankfully, she still seems happy to talk to me. Having just entered her 100th year when we meet, ‘The Last Woman of Steel’ has become a (Sheffield) National Treasure, a moniker that she shrugs off with true South Yorkshire humility.

The Women of Steel campaign is now well known in Sheffield, as visitors and locals alike pose for selfies by The Women of Steel statue in Barkers Pool - a celebration of all the women who had worked in the steelworks during both wars. “There were three others involved in the campaign,” says Kathleen - Kitty Sollitt, Ruby Gascoigne and Dorothy Slingsby - all of whom were in their 80s at the start of the campaign.

“Kit, she worked on her combustion thing, where sparks used to fly, and burnt her head. She’d hardly any hair because it had all got burnt off. There was Ruby, she worked on the bridge for D-Day, what did they call it, the Mulberry Bridge. Dorothy was a crane driver and I worked in a rolling mill at Brown Bayleys. I believe it’s a sports field now.”

“It took us, well must have been going on for nearly 10 years, and we just had a lovely journey and lots and lots of laughs, because Ruby, she was a natural comedian, always laughing.” Kathleen tells me.

Crone lesson 2. Make peace with death

We are at her retirement home in White Willows, Jordanthorpe. Her flat is bright and airy, despite my menopausal sweats and the sweltering heat outside. Her fridge freezer has just packed in, leading us to a discussion about the practical dilemma of buying white goods when you’re 100, and most likely won’t see out the three-year warranty. She’s just decided against replacing her sofa for the same reason,“Because whoever comes in after me, they might not like it.” she muses cheerfully.

It’s refreshing to meet someone who has so clearly made their peace with the transient nature of life and the reality of their own death, without any sign of regret or sadness. This is a ‘crone goal’ I’ve been in training for with my daily death meditations (‘If death is the only certainty, what kind of life should I lead?’) and various failed attempts to get through The Tibetan Book of Death and Dying. Kathleen, however, like so many women of her generation, doesn’t need the Death Cafes favoured by my cosseted generation, most of whom are so far removed from the process of death and dying.

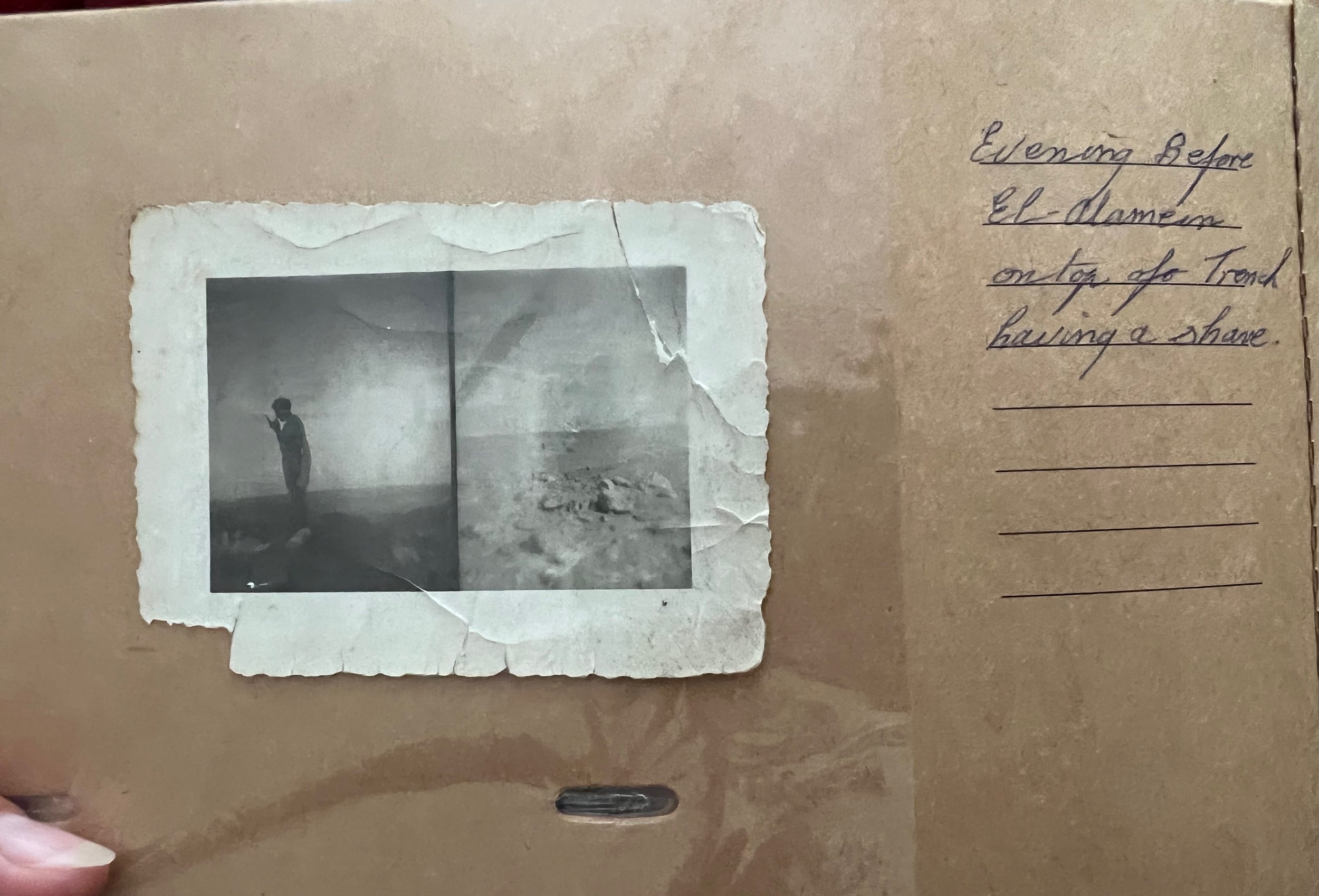

These are the women who were born in the aftermath of the first world war, and were teenagers, and then young women, throughout the second. A time when death was as much of a part of life as well…life. She gets out some pictures to show me. One is of her beloved husband, Joe, having a shave on top of a trench, the evening before the second battle of El Alamein. It’s so quietly poignant, it gives me a shiver.

“Joe said they smelt to high heaven. Well, they didn’t have any water in the desert, so they couldn’t wash, they were always on the move and they probably camped for a couple of days at an oasis. But Joe said they were absolutely alive.”

It’s not the first time I’ve heard how facing the immediacy of death can conversely make you feel the most alive you’ve ever felt. Reports of the battle of El-Alamein state very heavy casualties of over 13,000 British Allies (Source World History Encyclopedia) It did, however, turn out to be a “decisive victory for the British Eighth Army over Axis forces, marking a major turning point in the North African campaign of World War II.”

But while Joe would talk about his time in the desert, he would never speak about D-Day, where he was seriously wounded. “No way would he talk about that. He was so...he used to cry a lot after D-Day. And I mean, I thought that was awful because he’d seen lots of battles while he was in the Eighth Army. And it took just that one day…”

Crone lesson 3. Talk straight, but don’t moan

I want to bring us back to her time in the steelworks and I clock a book by Jojo Moyes on her bookshelf that I recognise. “Oh The Giver of Stars!” I say excitedly, before coming up with what I feel is the perfect segue: “Did you see any parallels between the sisterhood battling the patriarchy in that book, and your time in the steelworks?”

Katheleen thinks for a moment. “No, not really.” she says and we both laugh. Katheleen’s South Yorkshire directness is another crone quality to which many of us ‘crones-in-training’ aspire.

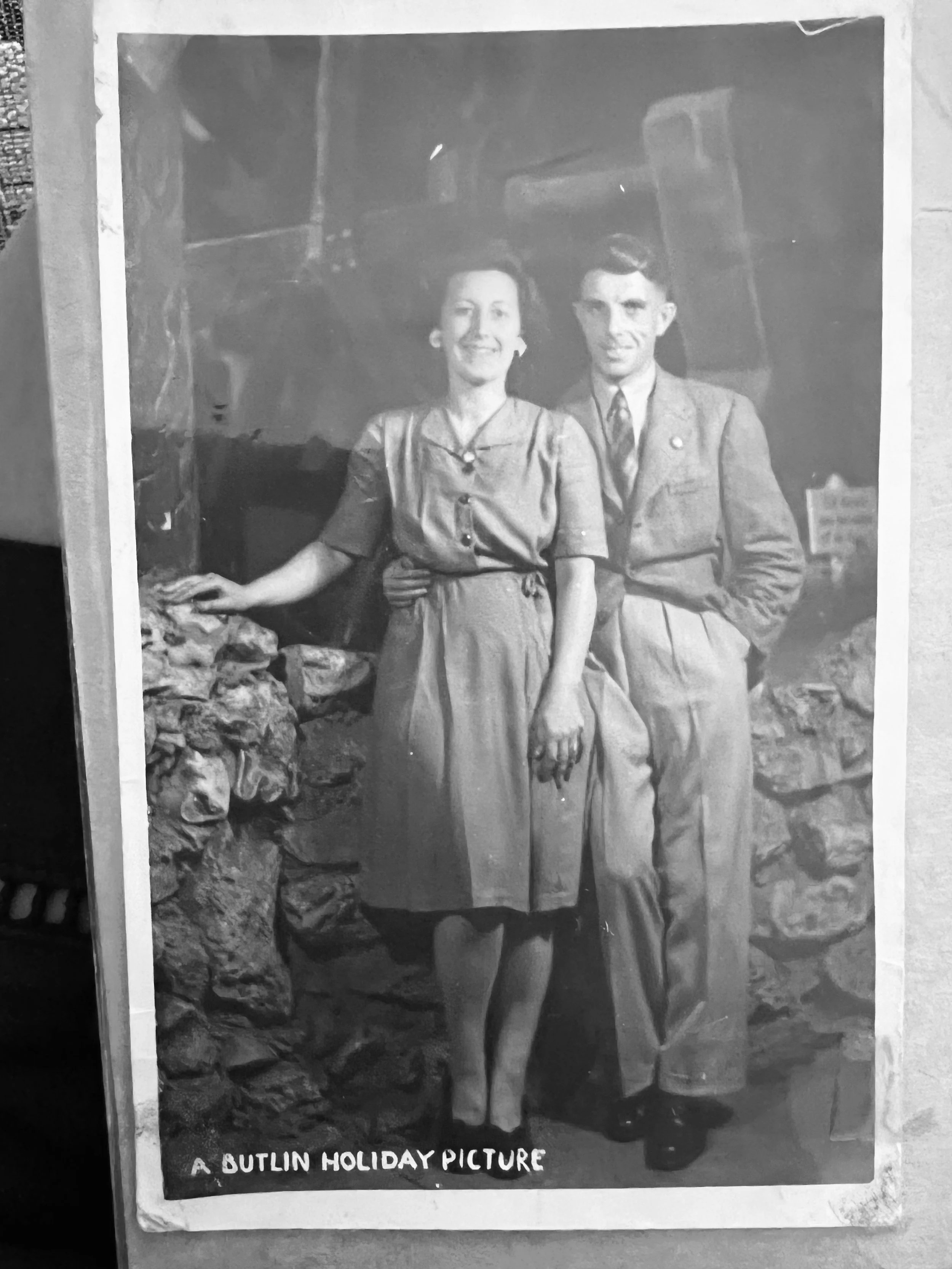

Later, when I read Michelle Rawlin’s wonderful book, ‘Women of Steel’, I realise that this straight-talking superpower has always been in Kathleen’s arsenal. In the book, Kathleen tells the story of her first date with Joe, not long before war broke out. They meet at the infamous lovers meeting place, Coles Corner (of course), and despite being brought up in Firth Park (“the posh side of Sheffield then”), Katheleen is so appalled by Joe’s suit that she just can’t stop herself blurting out: “Don’t ever wear that suit again — it doesn’t suit you at all!”

But there’s a time to speak, and a time to not speak, and moaning is something Kathleen has no time for. “That’s life, it’s always changed. It’s never the same. Yeah, don’t moan about your aches and pains. Just get on with life and take what suits you. Well, paracetamol suits me. So I take that. And I’m OK. I’m fine with that.”

Crone lesson 4. Acts of service and sisterhood.

Kathleen’s first steelworks was at Metro Vickers at Tinsley, where she tells me she was building ‘stators’ — round, stationary coils to be used in Spitfires.

Metro Vickers also had a hockey team, where Kathleen played right half. Her eyes sparkle as she speaks proudly of the team’s achievements. “I played hockey for Metro’s for years, even when I left, I played for them. Right half”.

“We were always in the Green Un.” she adds, proudly. (For the younger readers and Sheffield incomers who may not be familiar, ‘The Green Un’ was a Sheffield Saturday sports newspaper, printed on green paper, discontinued in 2013).

Kathleen tells me how, during the war, she used to send a copy of The Green Un every week to Joe where he had been posted - in the desert outside of Cairo. “Joe said the lads used to queue up for it when he’d finished reading it. You might think this is rude, but they said you would always see bits of Green Un flying around in the desert because they finished up as bum paper. They used to disappear with a shovel and a Green Un and he said they’d dig a hole you know, put the Green Un in. But they said the sand was always moving, and eventually this bit of Green Un would appear again.”

“What a way for them to show respect for your hockey victories!” I say and she smiles mischievously.

The job, however, came to an abrupt end. “I asked for a week off, because Joe and I were getting married. And my boss says, no, you can’t have it. Well, I said, I’m taking it because the government says I can. When I came back my boss was waiting for me and he got my cards in his hand and my P45. We married first of February, 1941 and he got posted abroad six months after and I never saw him for nearly four years.”

After being given her marching orders for daring to stand her ground with her boss, the Labour Exchange told her to go back, but she refused. “And that was when they sent me to Brown Bayleys for the crane driver’s job. And I said to them, well, I can’t do that because I have no head for heights! And there was another young lady waiting to be interviewed. And she took the crane driver’s job and we became quite good friends. And yes, she was one of the best crane drivers I think we ever had. I worked on the sheet rolling mill. I mean, those rolls were absolutely massive. And I’ve worked on the seven inch one. And I can’t tell you what they were for because I used to ask and my boss used to ask. I never knew.”

Learning the job was their first challenge. “When I first went to Brown Bayleys, the men wouldn’t show the women anything. Well, you just picked it up, sort of thing, you know. You watch what they were doing and you got on with it. You made lots of mistakes.There were lots of accidents. But eventually you did the job. And you were as good, sometimes you were better than them - because our fingers were more nimble. So we thought, right, we can manage without you. Because once women get their teeth into something…And we all supported one another because most of us had a husband or a boyfriend or a relative in the forces. And when we got to know someone injured or being killed, we all supported one another.”

During that time, she lived with her parents at Sheffield Lane Top, where they had two sergeant majors billeted on them. “The Bugler stood on our front lawn every morning blowing the Reveille at 6 O’clock. So they woke everybody up! But we just got on with it, you know. They loved being up here in Yorkshire - it was mostly fields where we lived and they just loved the peace and quiet. And my dad loved having them because, coming from London, they were very fond of the theatre. And they used to go to the stage door of The Empire to talk to whoever was on. And if my dad was around, because he was a steelworker and he did shifts, they’d take my dad with them. And he had a wonderful time.”

Kathleen paints a vivid picture of Sheffield during the war including dances at Cutlers Hall (“downstairs was old-time dancing and upstairs was modern dancing”) and the Americans teaching them the jitterbug. “They used to throw the girls around and see everything they’d got oh dear! But if they heard music, they were in! And we had some French soldiers. They were very polite. If you went to dances, they would be quite loving while you were dancing! But I didn’t get to go a lot because of shift working. And very often if you went into town to a dance, you most likely had to walk home.”

I ask her about the Sheffield Blitz - was it scary?

“I was at work, I was on nights. We worked through the night. We knew they were over the coast because when the Germans crossed the coast, all the lights in the factory went blue, dark blue. But we had to carry on working. We couldn’t stop the machines.

And my dad was on nights. He worked at Steel, Peech and Tozer. They worked on the furnaces and when they were casting, it was bright red. You could see it. So that night they had a lot of help because they could see them from the furnaces and all the works. On Thursday night, they flattened the Moor. And then on the Sunday night, they started where they’d left off. And they did the Wicker, and all that way. But, he didn’t bomb us. We were very lucky. We used to hear them going over night after night and you could look up at the sky and hundreds of black planes going over and we got used to it and we didn’t bother going in the shelter…you always knew it was the Germans because their planes had a sound like no other.”

Crone lesson 5. Focus on what you can change, (and don’t waste time on the things you can’t).

Throughout our chat, I’m struck by Kathleen’s ability to make peace with the things she couldn’t change, but stand her ground for the things she could. I asked her how she felt when the men came back from the war, and the women were unceremoniously ‘let go’ without so much as a thank you. “I can remember in my last pay packet at Brown Bayley, when I opened it there was a note inside that said we no longer require you. No ‘thank you’. But I mean the men were coming back from the war. Well it was only fair they wanted their jobs…” I marvel that there is no resentment or bitterness in her voice about a situation that they could do nothing about at the time.

However something was done, many years later, when Kathleen famously sparked the Women of Steel campaign in 2009 with a phone call to The Star. She was watching a programme celebrating the Women’s Land Army, and was feeling furious that women like her, who had worked in the steelworks during the war, were still missing from history.

We move onto more recent history, and are now in a discussion about Putin (“I wish someone would just pop him off”) and China (“We don’t want a war with them either,”) though Kathleen, like so many of us, says she has “fallen out with politics”. “Well, I’m too old now to really bother about it, because I mean, at my age, I haven’t got a lot of time left… I’m cheesed off with it. I worry for my grandchildren though…My time on earth is getting shorter… but life just goes on, doesn’t it? And it’s continually changing. Sometimes it’s for the better…but mostly not!”

Again, we both laugh, and I am struck by her straightforward wisdom and acceptance of impermanence and not wasting time on the things that we can not change. “I’ve got two daughters. They’ve both got their families and they live their life like I and Joe did, but also they do things differently. I never interfere because my time on earth is getting shorter and because they’ve got their life to live.”

Crone lesson 6. Love deeply.

“I still talk to him everyday.” says Kathleen, gesturing at a framed picture on the sideboard of her beloved Joe who died in 2008. “These days, sometimes I even swear”, she confesses with a cheeky smile. We both agree that Joe would understand given the exceptional circumstances of the current climate.

“When Joe came home he needed a lot of looking after because he suffered from combat stress. It took just one day for him on D-Day to practically mentally finish him off you know, just fall to pieces. And there wasn’t the help there. He was 80 before someone came from the War Department to see how he was…”

She shows me a picture of her and her daughter visiting Ver-Sur-Mer on Remembrance Day. They were standing by the very sea wall where Joe had been placed, injured, and she swore she would feel him shaking her. “It was just as though Joe had got hold of my shoulders and he was shaking me. I could not stop shaking from head to toe and I was crying at the same time because I felt… a closeness of Joe…whether it was I was thinking so deeply about that that caused it or whether it was Joe shaking me I don’t know…Do you think such things can happen?” She asks. I nod. “Yes, yes, I do.”

Kathleen goes on to tell me about a girl who worked at the little cafe on Gold Beach, “She said to my daughter and I ‘do you know? We hear those boys most nights walking these beaches.. and whistling, like the boys used to whistle…They sweep the sand every night, but she said the next morning, there’s always footprints in the sand’…”

Crone lesson 7. Keep doing what you’re doing for as a long as you can.

I ask her about what lessons life has taught her and what advice she would give women. “Keep doing what you’re doing for as long as you can. Just because you’re getting old, don’t ditch things, carry on doing them. That’s my philosophy. I mean, up to a year or so ago, if anybody had said to me, will you come and play right half in my hockey team? I’d have said yes.”

“Joe and I used to do a lot of walking. And I had a job keeping up with him because he was in the infantry. They march very quick, so many steps to a minute and I used to be shouting, “wait for me Joe!” Both my girls are the same. They both walk quick. When they see me now, I get off and they say, look at her she’s off again, walking quick, like him.”

“I don’t have carers, not as yet, probably someday I will have to. For now, I shall look after myself.”

Crone lesson 8. Invest in the best haircut you can afford.

Our interview takes place one month before she is to receive an Honorary Doctorate of Engineering from the University of Sheffield. At 100 years of age, she will be the oldest recipient of a University of Sheffield honorary degree. Kathleen shows me the letter, but there are more pressing matters on her mind - avoiding the ‘one-cut-fits-all’ fate of the visiting hairdresser.

“People come out of that salon and they all look alike to me. I don’t like my hair like a lot of older people do. They like it really curly, frizzy and they like perms. I like my hair to be called modern. I’ve never had a perm in my life. I’ve got two crowns as well, so it needs a professional cut…I am fussy about my hair.” she laughs.

She’s chuffed though, because her daughter, Julie, has just managed to get her an appointment at her favourite salon on Bocking Lane in time for the ceremony.

I ask if I can take a selfie, which we both then review disapprovingly - Kathleen wishing I’d come after she’d been to the hairdressers, me marvelling at my multiple chins and menopause bingo wings. But for the last time that day, Kathleen sets me straight with a final piece of wisdom.

“No, nowt to worry about such things. You are what you are, and if people don’t like it, say, right, buzz off.”

There’s one final piece of order - the publicity consent form - which she signs and dates, apologising for her shaky handwriting. When it comes to the ‘age’ box, she writes ‘Age 100’ and we both fall silent, gazing at the enormity of such a number. Kathleen smiles.

“Blimey. 100 years old.

How did that happen?”

Epilogue

It’s now 2025 when a picture in my social media feed makes me stop scrolling. It’s of Kathleen in her doctorate gowns and mortar board. She has just died, age 103. I remember the sparkle of mischief in her voice, and our hairdressing chat about her two crowns.

What luck she had two crowns, I think. One for her beloved Joe, and one for the Queen Crone of Steel, one of the last remaining women from a generation to whom we owe so much. I hope the two of them are now walking (at pace) arm-in-arm across the desert together, Joe bending occasionally to pick up a tiny piece of the Green Un, and presenting it to her like a flower, then in the morning, nothing but footprints in the sand.

Want to read more articles like this and get one straight to your inbox each month? Sign up to our Substack ‘Tits to the Wind’ here. First three are free, then just £4 a month to support all the work we are doing.